What are professional development communities?

Professional Development Communities are characterised by a number of things:

- Opportunities for teacher growth are seen as development opportunities. Usually this Professional Development is delivered by someone in a position of power whether because of their position or because of their knowledge. Teachers can increasingly become more dependent on a few who have specific technical knowledge and know how – often on those outside their schools and centres. It can become disempowering and learning tends to be passive in these situations.

- In-School Development is in most cases, although not in all cases, undertaken after school – or outside normal teaching hours. Teachers may come to see it as an ‘extra’. As an additional burden. They may also see Professional Development taking away from them valuable time which could be more effectively spent doing other things.

- Professional Development initiatives use ‘contrived collegiality’ as a basis for teaming. Leaders literally force teachers who do not necessarily want to work together to work together in developmental areas they may not have that much interest in developing. This can damage relationships between teachers and leaders and teachers and facilitators. Without relationships leaders and facilitators struggle to influence. Relationships lie at the heart of being able to influence outcomes in positive ways.

- Other examples of contrived collegiality include Learning Circles, Staff Meetings, Team and Department Meetings and Appraisal.

- Off-site Professional Development is attended by a few specially selected participants who have the almost impossible task of returning to school to deliver the key messages. Often this becomes too difficult so that new ideas and thinking frequently do not become part of a new school landscape.

- In-School Professional Development is usually decided by one, or a few, with more power, on behalf of everyone else. This is founded on a ‘we know what’s best for you’ belief. Over time it becomes ‘paternalistic’ and can disempower teachers and the teaching profession.

- Teachers can feel as though they are being treated like children when they have the freedom to choose, removed. Over time, teachers can start behaving like children as a consequence. They can become increasingly more dependent on others and increasingly more resistant. Both are childlike transactions.

- When the notion of ‘choice’ is removed from teachers Professional Development comes to be seen as compliance. It has been said that saying ’yes’ is meaningless when the choice to say ‘no’ has been removed.

- Motivation for Professional Development for teachers is usually extrinsic – they are asked to ‘buy in”. School leaders can become incredulous when after time, effort, money and resources they disbelievingly see teachers resist. They have been unable to shift, through the Professional Development initiative, teachers’ motivation or willingness to participation. Often the harder school leaders push Professional Development the harder teachers push back. Often this resistance is passive. Teachers are waiting to see the latest ‘band wagon out’ before the next one comes steam rolling through.

- Despite the culture of your school you can always offer Professional Development. Professional Development happens despite your school’s culture. It’s easy because it is forced.

- The vast majority of Professional Development provides informational learning opportunities – referred to as ‘shallow learning’ or ‘technical learning’ or ‘single loop’ learning.

- Teachers can feel as though they are being ‘nagged’, ‘manipulated’ and ‘pushed’ into undertaking teacher development which many may feel they don’t need.

- Professional Development in the vast majority of cases does not make teachers better people; it’s designed to make teachers better teachers. Teachers can come to believe they are machines, valued for only their teaching, and not for who they actually are as human beings. Outside the education sector good employers also recognise their obligation to invest in their people to make them better people. As one teacher commented: “I have a friend who works in a bank and although she earns less than me she gets opportunities to develop technical skills which relate to her role directly but she also gets to attend courses which also allow her to develop herself in ways which she can transfer out of her job into her everyday life. I’ve been teaching for 7 years and all I can recall are Numeracy, Literacy and Formative Assessment. It’s quite depressing really to think my two Principals so far haven’t been able to see me as anything other than a teacher. It makes me think they don’t in their hearts really care about me as a person.”An over reliance on Professional Development as a vehicle for enhancing teaching practice is limited Whilst easy to set up and deliver, research continuously highlights its impact on embedding change in teaching practice is severely limited. As well as the reasons highlighted above, which have a significant impact on the attitudes and thinking of teachers, there are at least four other things we need to know about Professional Development:

- Michael Fullan highlights the ineffectiveness of Professional Development in his book Leadership & Sustainability (2005) when referring to the long term disappointing results of Numeracy and Literacy Projects in the UK between 1997 and 2003 despite the billions of pounds spent on them.“Billions of dollars have been spent on education reform in the past decade and a half …(globally)… with results in literacy and maths, at best inching forward. This is not value for money, nor is it satisfying work for teachers, principals, students, and parents … along with many others, we believe that the current model …(of raising student achievement0… is in need of change – change that will transform practice.” Michael Fullan, Peter Hill & Carmel Crevola (2006)

- Fullan & Andy Hargreaves in their book What’s Worth Fighting for in Your School (1996) note “there are always things to be done, decisions to be made, children’s needs to be met, not just every day, but every minute, every second”. This “pressing immediacy” means that even if teachers want to implement some new programme they may not have the energy necessary to put it into practice.

- In many cases there is the sheer number of competing programmes. Even if the teacher does have energy to learn new things and the emotional resilience necessary to implement and change, often the sheer volume of change initiatives they are expected to oversee and engage in is suffocating. Many leaders seem to work on the assumption that more is better. The tendency is to offer more and more new practices without developing effective supports for those practices. Most teachers face a menu of too much Professional Development with not enough quality support. They are expected to implement, ICT, Numeracy, Literacy, Technology, Formative Assessment, Inquiry and Health initiatives amongst the myriad of others usually without necessary support and sometimes at overlapping times. It can mean that a teacher could be expected to be engaged in 2 – 6 initiatives at any one time. Each intervention, properly supported could make a difference in students’ lives but when intervention is served up with no attention to implementation planning, teachers begin to feel overwhelmed. Eric Abrahamson (2004) referred to this phenomenon as “initiative overload” – the “tendency of organisations to launch more change initiatives than anyone could reasonably handle”. When faced with “initiative overload”, Abrahamson says, “people …begin to duck and take cover whenever they see a new wave of initiatives coming”. In his book, Managing at the Speed of Change, Darryl Connor puts it this way: “as the number of changes multiplies, and as the time demands increase, people approach a dysfunction threshold, a point where they lose the capacity to implement changes’.

- Research has been showing for many years how traditional forms of Professional Development are not generally effective, usually getting no better than a 10% (Bush 1984) implementation rate. This means that a school investing $100,000 on Professional Development over a 5 year period could be spending close to $90,000 on lunches. The tax payer gets a $1, 000 return.

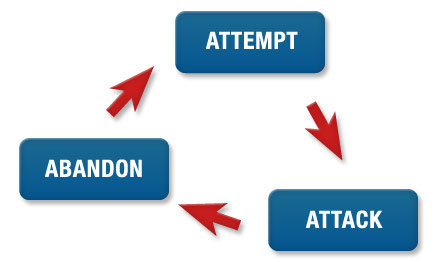

Thousands of teachers’ stories conducted by researchers over many years reinforce what research consistently tells us. Teachers are unanimously critical of one-shot programs (this may include workshops over a period of time) that fail to address practical concerns. Teachers criticise training that lacks follow-up and fails to recognise their expertise, amongst many things. The traditional model of teacher development of an expert talking to a room full of strangers has been described by Jim Knight (2007) as being sometimes ‘literally worse than nothing’. Research shows this type of staff development often leaves teachers frustrated, disappointed and insulted – feeling worse off than before the session. In essence, this type of approach treats adult learners like children where leaders are saying to their staff “we know what is best for you”. The worst consequence of this type of traditional form of professional Development is that it can erode very quickly teachers’ willingness to embrace new ideas and over time, a cycle of ‘despair’ can develop within a school. This is a significant blockage to developing a community of professional learners.

Knight. J , Instructional Coaching, (2007)

Knight. J , Instructional Coaching, (2007)

When school leaders see programmes failing to gain momentum as quickly as they had hoped or they see programmes which offered so much failing to deliver on all they promised, they naturally start searching for reasons as to their failure. Not surprisingly, teachers are often blamed for ‘resisting change’. Teachers respond in type by blaming the leadership, telling each other this bandwagon, like all the rest, will also pass whatever new innovation is introduced. Thus what can develop is a vicious cycle of blame and resistance. Leaders increasingly express their frustration with teachers who resist change and teachers who experience professional development programme after professional development programme adopt apathy as a cultural norm. Quite clearly traditional ways of engaging teachers in professional growth and development are not palatable for any government particularly with the new austerity brought about by new global economic realities. Governments and taxpayers are quite rightly seeking ‘bang for buck’ from the public purse and Professional Development quite rightly is in the firing line.

An over reliance on Professional Development also has unintended and hidden consequences in our schools and centres. Over time rather than letting people take responsibility for addressing their problems – that is they get involved in coming up with shared solutions – teachers feel they are force fed new programmes. Thus a “shifting the burden to management” takes place. Professional Development undertaken in this way may capture the hearts and minds of a few for a time but these gains don’t stick. Worse, this approach makes teachers passive as they come to depend more and more on their leaders and managers to solve their problems and ‘take care of them’. The more dependent they become the less they are able to feel a sense of responsibility and get involved in grappling with their problems. They default to “shifting the burden to leaders” – for many complexities they face. The blame game starts. This ‘sheep dip’ approach to bringing about school improvement – standardised for the masses – completely ignores employees’ true potential for making their own decisions and managing their own issues. Shouldn’t trusted professionals have the ability and where withal to be able to determine where they are going wrong and how to rectify any issues? ‘Sheep dipping’ has another unintended consequence. Because it makes people passive it discourages the fluid transfer of knowledge that occurs when people feel involved in and responsible for their work. Unfortunately, with ‘sheep dipping’ approaches, instead of looking to one another, anticipating needs and collaborating as a team, teachers have their eyes on management, waiting to be taken care of. Knowledge remains trapped in individuals’ minds and in separate areas/teams within schools and centres. Leaders are significantly inhibited from ever leveraging the true potential of their people. So leaders push harder. And they become seen as more significant enforcers – not influencers. It becomes a vicious cycle and without knowing it, educational leaders fall into the trap of believing they have developed their schools and centres and centres as profound and robust Professional Learning Communities without realising that they have created nothing more than Professional Development Communities – which have left their teachers possibly disempowered, frustrated and scarred. They switch off from wanting to learn and often try and lose themselves in their classrooms. It is questionable at this juncture whether or not the school is also a community if teachers start to isolate themselves.

This ‘industrial’ model of teacher development now no longer fits the new era we are entering. It assumes many things which quite simply are flawed. For example leaders assume:

- Our teachers can see what we see and will understand the need for change if we tell them what is required.

- Our teachers are primed for learning. All we need do is deliver the materia, and they’ll do the rest and engage.

- All our teachers have exactly the same learning needs and developmental areas.

A new era is upon us.

Find us on Facebook

Find us on Facebook